Here we see the corner of Joralemon St and Clinton St., Brooklyn, then on the edge of Red Hook. H.P. Lovecraft lived just a short walk from this spot, in a “dismal hovel” at 169 Clinton St., also right on the edge of Red Hook. During his time here he…

often” ate at “Peter’s in Joralemon St.” (Selected Letters II)

Thus he may have known the corner well, as he often walked down from his apartment and around the corner to eat in a Joralemon St. cafe. Joralemon St. goes both ways from the intersection, as you can see from the map below. Since the precise cafe location is currently unknown, then the direction in which he would have turned off Clinton St. is also unknown.

The photographer was Percy Loomis Sperr, and the date is 22nd February 1930. Which is only a few years after Lovecraft had left.

As for Lovecraft, the man seen walking into the right of the picture, or the man seen on the left contemplating the wasteground, both seem like close stand-ins for him (perhaps they’re Sperr’s bodyguards, which a cameraman with a valuable camera and tripod might need in Red Hook). Although by this date the master was safely back in Providence, and musing on the opening lines of “The Whisperer in Darkness”.

Here’s my useful map for future researchers in this part of Brooklyn. I used Photoshop to combine four such maps, which show building-level numbering and street layout. It’s centred on Lovecraft’s 169 Clinton St. Bear in mind that it’s from 1884, so is only to be used for initial orientation. Specific details for your chosen time period will need to be confirmed by consulting later maps.

It seems that Clinton and Atlantic broadly formed the boundaries of what was then thought of as Red Hook. Which means Lovecraft was living right on its edge. Evidently it was not a salubrious edge. Lovecraft’s decrepit mouse-infested lodgings were noisy, smelly, and the apparently genteel Irish landlady quickly proved to be none too particular about who she took in as lodgers — an adjacent room harboured shifty youths who stole Lovecraft’s clothes and left him only what he was wearing.

Below Columbia St., seen along the very bottom of the map, the long waterfront of sailor-bars and wharfs and warehouses began and ran down for a few blocks before thrusting out into a series of ship-piers. Experts on the waterfront’s history say little online about the 1920s and 30s, but can say that until the public works of the mid to late 1930s there were still shantytowns, open scrubby land and undrained marshland along the waterfront. Eastern parts of Red Hook were also heavily dotted with “weedy undeveloped terrain” on 1924 aerial photography, and a Thomas Wolfe short story of 1936 (which concurs with Lovecraft’s description of Red Hook) would put this area at “Erie Basin”.

Searches of Google Books reveal that, back of this waterfront area, the built-up residential part of Red Hook seen on the above map mostly had a population of poor Italians from the south of Italy, split into dialect groups that had great difficulty comprehending each other. Red Hook also had some large, though possibly dwindling, Irish groups until the later 1930s. Further there were significant numbers of Syrians who were almost all Christians escaping persecution, according to the book An Ethnic and Racial History of New York City — although Lovecraft wasn’t to know that from listening to their “eldritch” music through the walls of his apartment. There were even a few old Norwegians and Finns (classed as “Swedish” in reports), left behind after earlier waves of immigration had left the area c. 1900-1910. Presumably many of these remainers were old sailors and this may especially interest some, in terms of Lovecraft having a Norwegian sailor be central to the plot of The Call of Cthulhu. Mixed in with Red Hook’s two majority populations of Italians and Irish were floating populations of active sailors on shore-leave from all over the world. There was a small permanent Caribbean population in Red Hook at 1920, perhaps families of sailors, and these may be the same as those noted in a 1927 report as being tiny colonies of Porto Ricans and black Brazilians. Mingling among the transient sailors were the many illegal arrivals, spurring occasional raids into Red Hook by the immigration authorities. In “Red Hook” Lovecraft thus appears to have got the demographics right, except that he substituted the Spanish (not yet in Red Hook, at that time) for the Irish. Presumably he made this change because his detective protagonist is Irish.

One academic has claimed in the New England Review that Lovecraft was right about there being Kurds in Brooklyn, the claim being based on the rather idle assumption that the modern Kurdish community has always been there. That is not the case. The current Kurdish community only arrived there in 1975 when the U.S. resettled 700 people. Brooklyn’s Kurdish Library was opened in 1989 and by the early 1990s there was a community of 2,000 (Encyclopaedia of New York City). Thus the modern community, centred on North Gowanus which is now Boerum Hill, cannot plausibly be ‘mapped back’ onto any Kurds Lovecraft might have encountered in Brooklyn in 1925. Indeed, Lovecraft correctly states in “Red Hook” that Gowanus was then home to a relic population of Norwegians. I can add that there had been a failed Sheikh Said rebellion of the Kurds in February-March 1925, and this might just have caused some richer Kurds to try to get to New York City. “The Horror at Red Hook” was written 1st-2nd-August 1925, and thus Lovecraft might had seen and felt a small but noticeable influx of exiled Kurds entering clandestinely into Brooklyn in May-June-July. But that is speculation, and I can find no confirmation of any newly-arrived Kurds in Brooklyn in 1925.

On the area S.T. Joshi remarks, in I Am Providence…

It [Red Hook] was then and still remains one of the most dismal slums in the entire metropolitan area. In the story Lovecraft describes it not inaccurately, although with a certain jaundiced tartness:

‘Red Hook is a maze of hybrid squalor near the ancient waterfront opposite Governor’s Island, with dirty highways climbing the hill from the wharves to that higher ground where the decayed lengths of Clinton and Court Streets lead off toward the Borough Hall. Its houses are mostly of brick, dating from the first quarter of the middle of the nineteenth century, and some of the obscurer alleys and byways have that alluring antique flavour which conventional reading leads us to call “Dickensian”.’

Lovecraft is, indeed, being a little charitable (at least as far as present-day conditions are concerned), for I do not know of any quaint alleys there now.

Photographs show large parts of Red Hook being erased by massive ‘housing projects’ (UK: ‘tower blocks’) in the late 1930s, so the alleys Lovecraft evoked may once have actually existed.

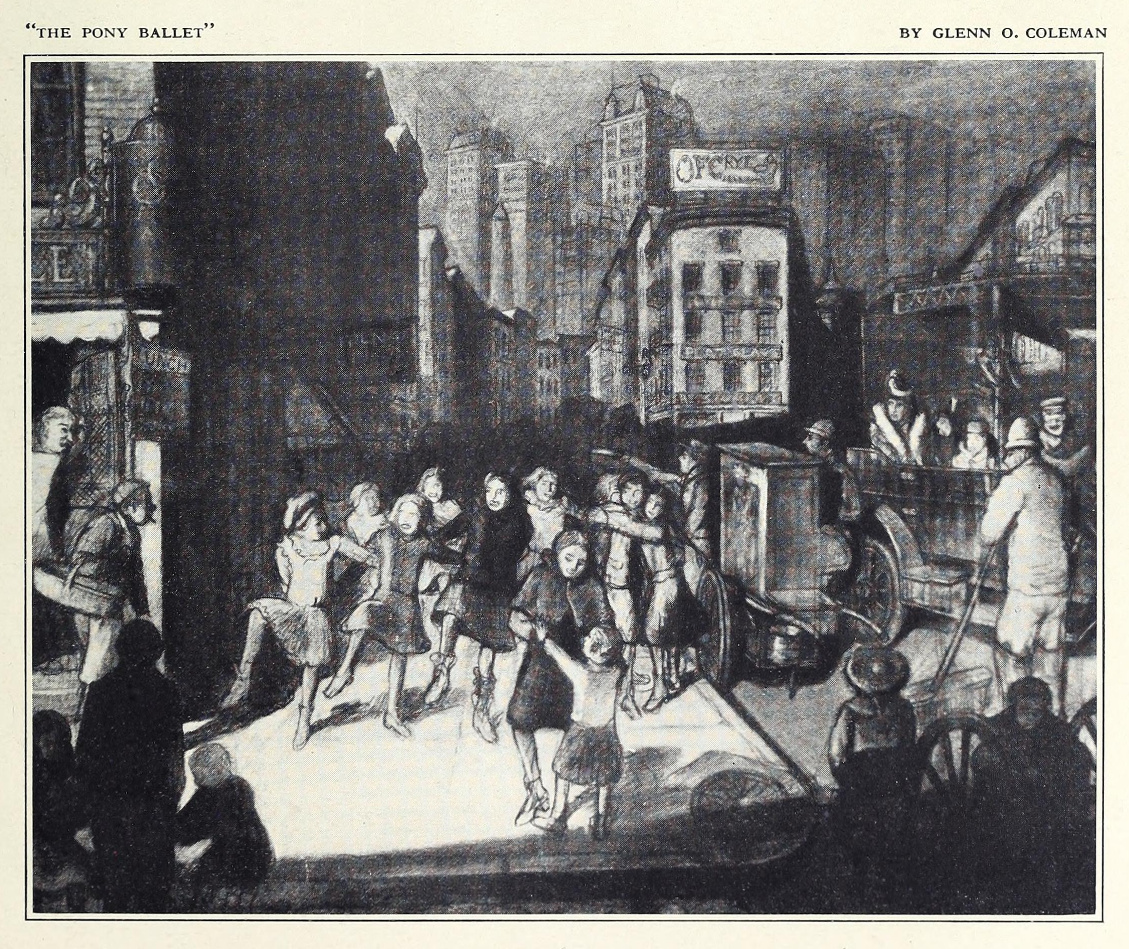

I’ve given the opening picture of Joralemon St. and Clinton St. a new light colorisation. Architectural record photographers such as Sperr tend to prefer very quiet times to make pictures, and we can thus assume that at other times this scene would have been alive with children, food-carts, vehicles, pedestrians, and other obstructions to making a record-picture. Here is a 1923 picture indicative of the sort of Italian/Irish New York street-corner life Lovecraft would have had to weave his way through to reach his cafe. Though one imagines that the affluent lady in the open chauffeur-driven car would have been a rare sight, in that part of New York…

Picture: Glenn O. Coleman, “The Pony Ballet”. A pony ballet was a very high-kicking chorus-girl dance-line, presented on the stage by the younger dancers in a theatre troupe. It usually formed an interlude between acts at a variety theatre.

In terms of the appearance of the streets we should also take into account the extreme weather in New York City during Lovecraft’s time there, which would seasonally have radically changed the nature of the streets. Such as the worst snowstorm in living memory from 1st-3rd January 1925. Lovecraft had barely moved in to his “dismal hovel” at 169 Clinton Street, on 31st December according to the date I have, before the storm hit the city. Then a searing killer heatwave settled on the city in June of 1925. There was a similar but slightly less searing heatwave in July 1926, though by that time Lovecraft had left New York. Worse was to come, as can be seen from this EPA chart, but Lovecraft was able to enjoy these in far more comfort. Indeed, it might be said that without the 1929-37 heatwaves, he would not have lived as long as he did…

Pingback: Friday picture postals from Lovecraft: Fulton St. near Clinton St., Brooklyn. | TENTACLII : H.P. Lovecraft blog

Pingback: Friday picture postals from Lovecraft: Fulton St. near Clinton St., Brooklyn. | Tentaclii